Op Art’s Tricky Legacy

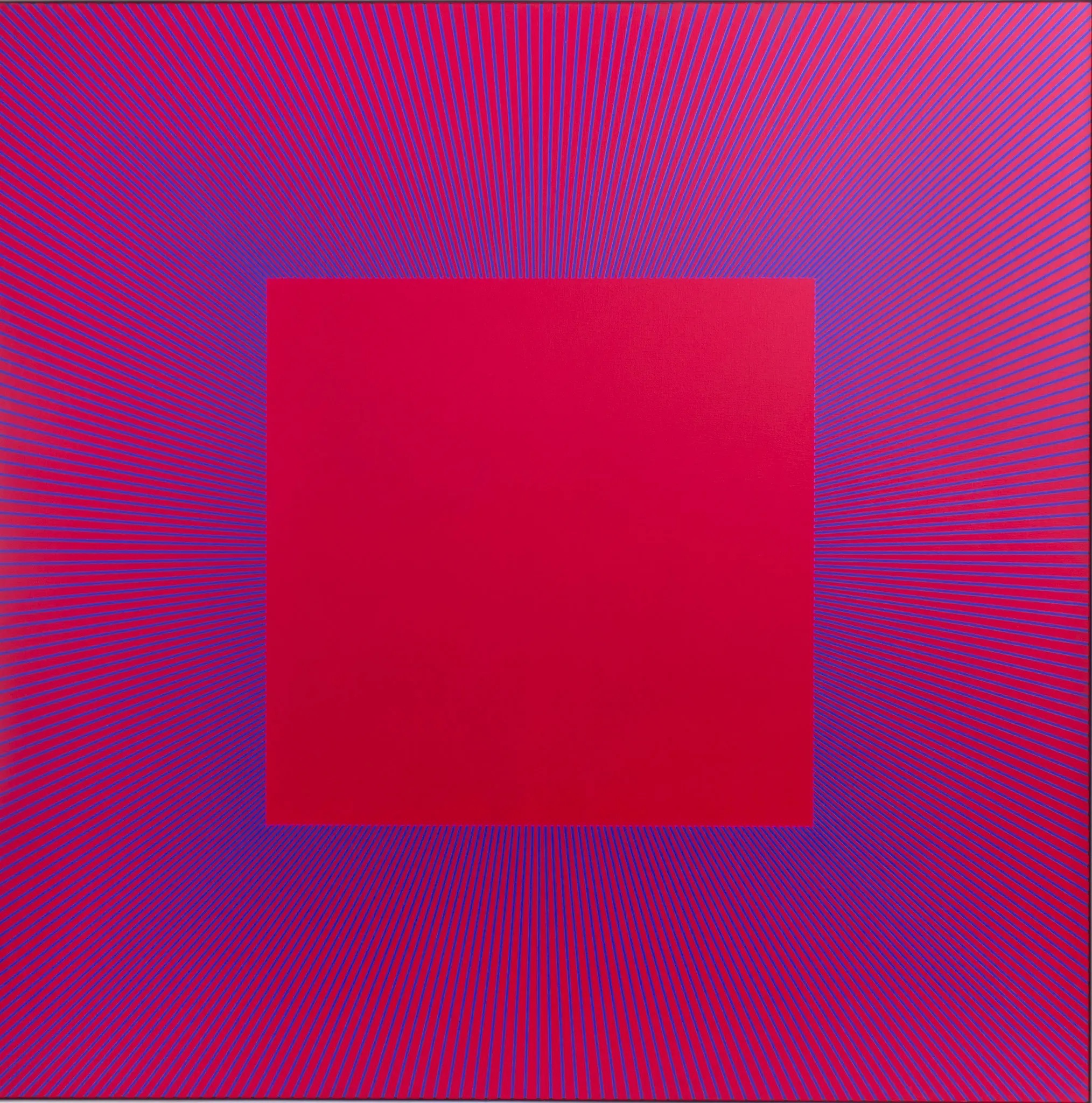

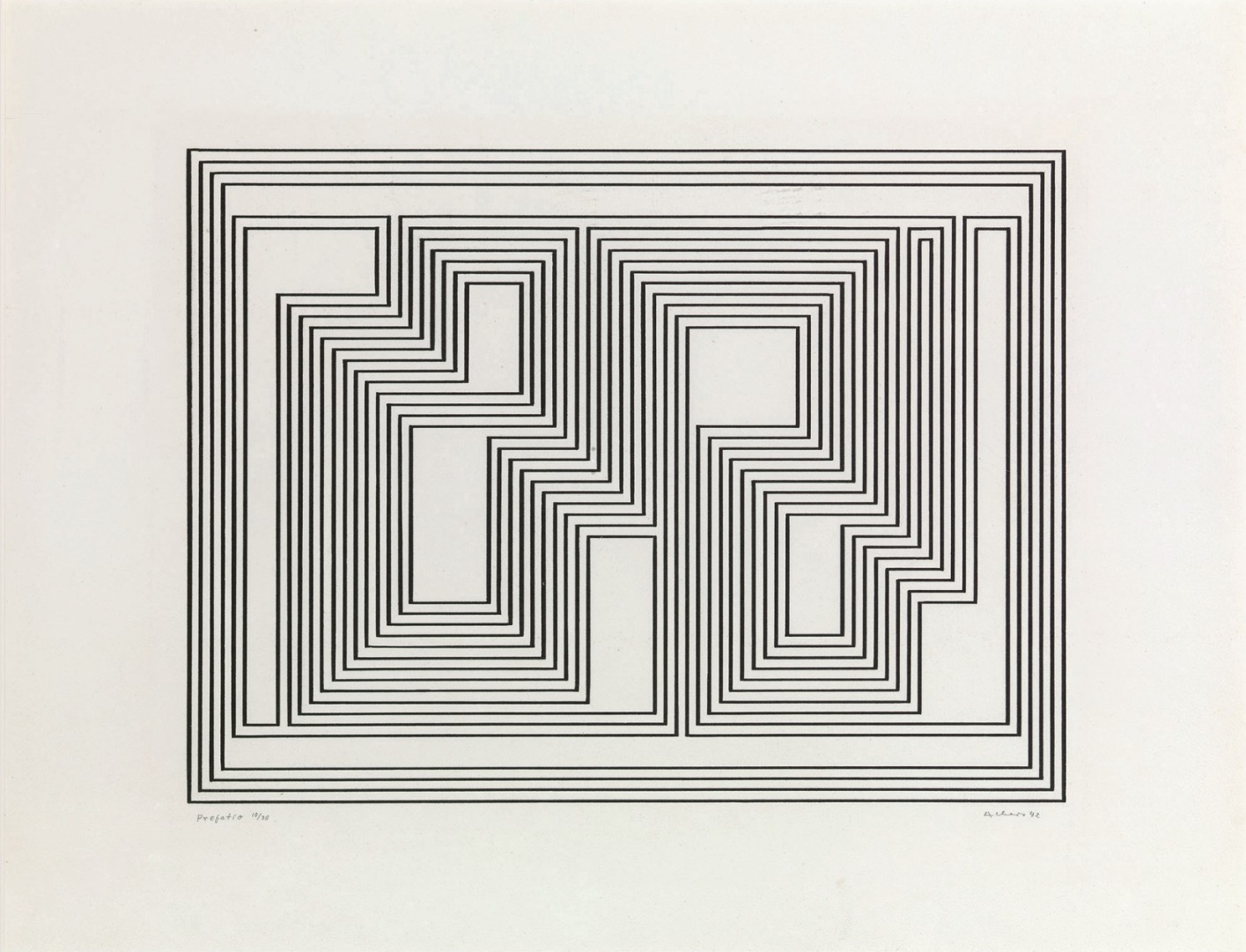

The genre of Op art has always been difficult to see clearly. To all appearances, it is a type of art that revolves around optical illusions- often utilizing contrasting colors, repetitive geometric forms, and moiré patterns. The genre found its roots in movements like Bauhaus, Cubism and Dadaism. During the ’60s, it also overlapped with other styles, like Geometric Abstraction and Kinetic Art, making the boundaries of the genre (like many things in the ’60s) a bit hazy.

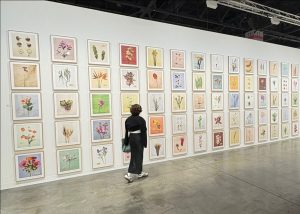

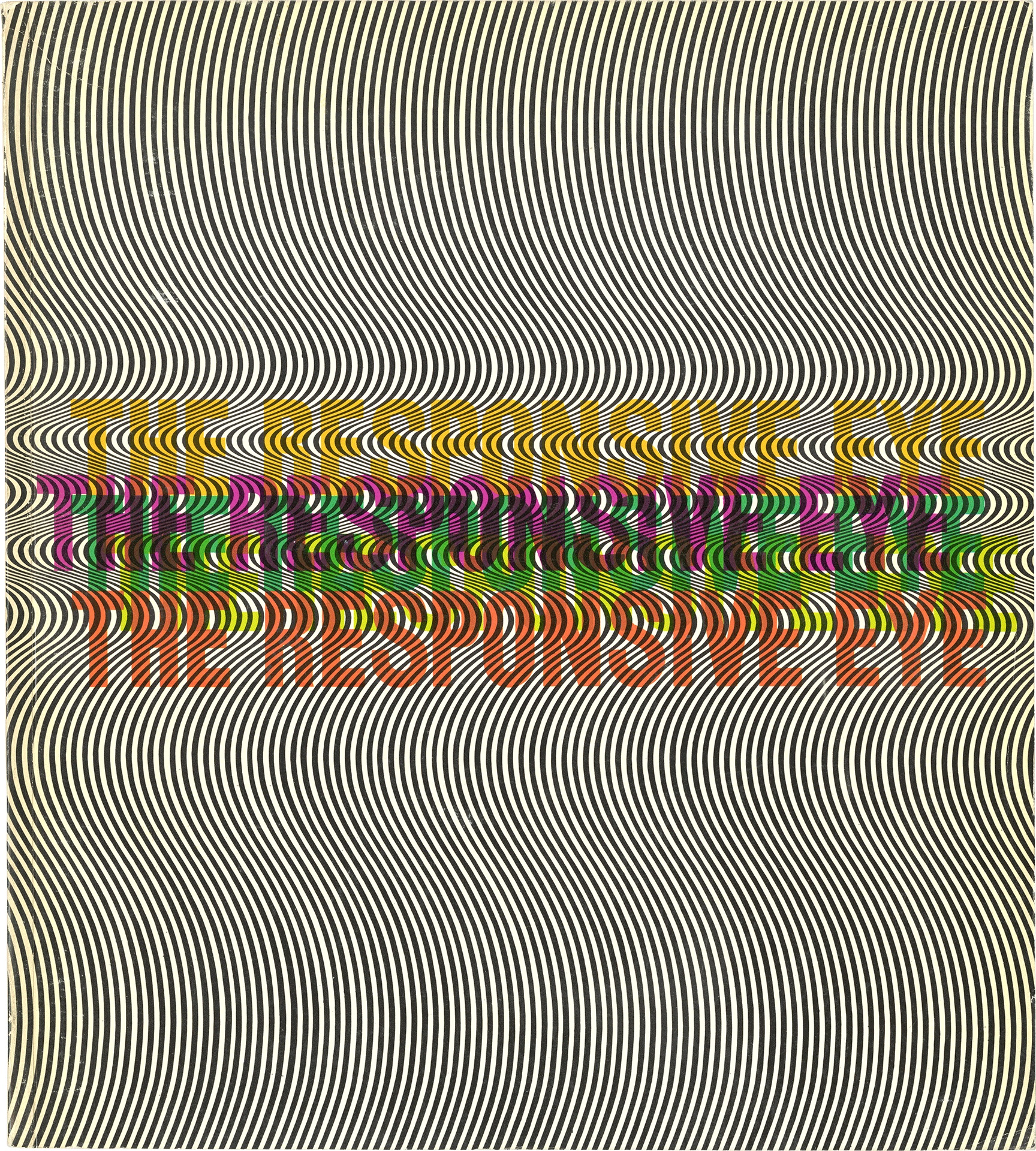

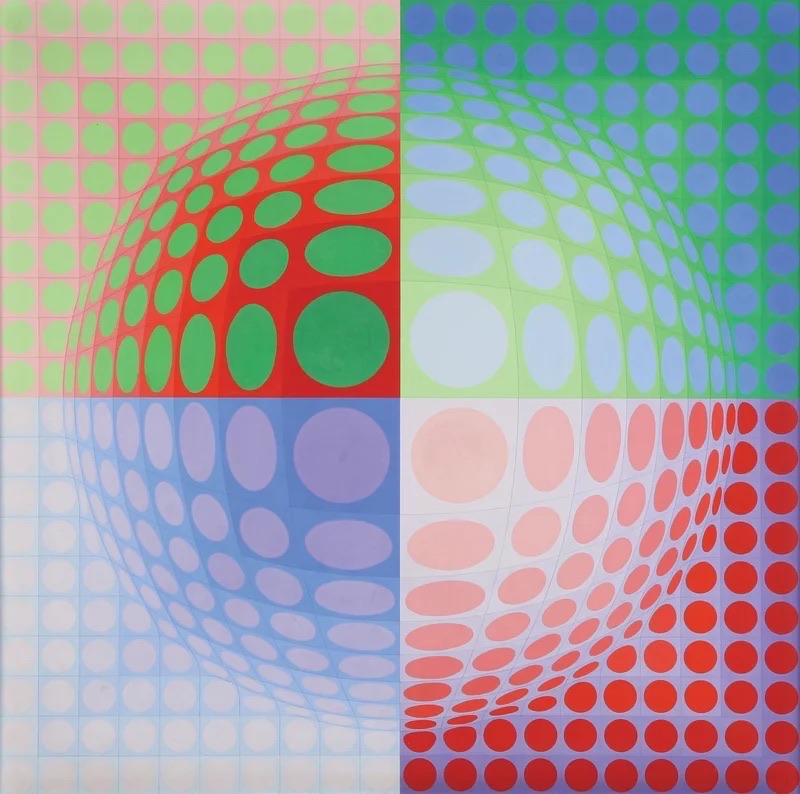

The term came into widespread use when curator William Seitz brought works by international artists to the MoMA in the influential exhibition The Responsive Eye (1965). Seitz selected artists that were researching the various ways the eye responds when certain visual elements converge on the canvas. The exhibition included early forerunners of the genre like Hungarian-French artist Victor Vasarely and American Josef Albers, while its core was composed of Op icons like Richard Anuszkiewicz, Yaacov Agam, and Bridget Riley.

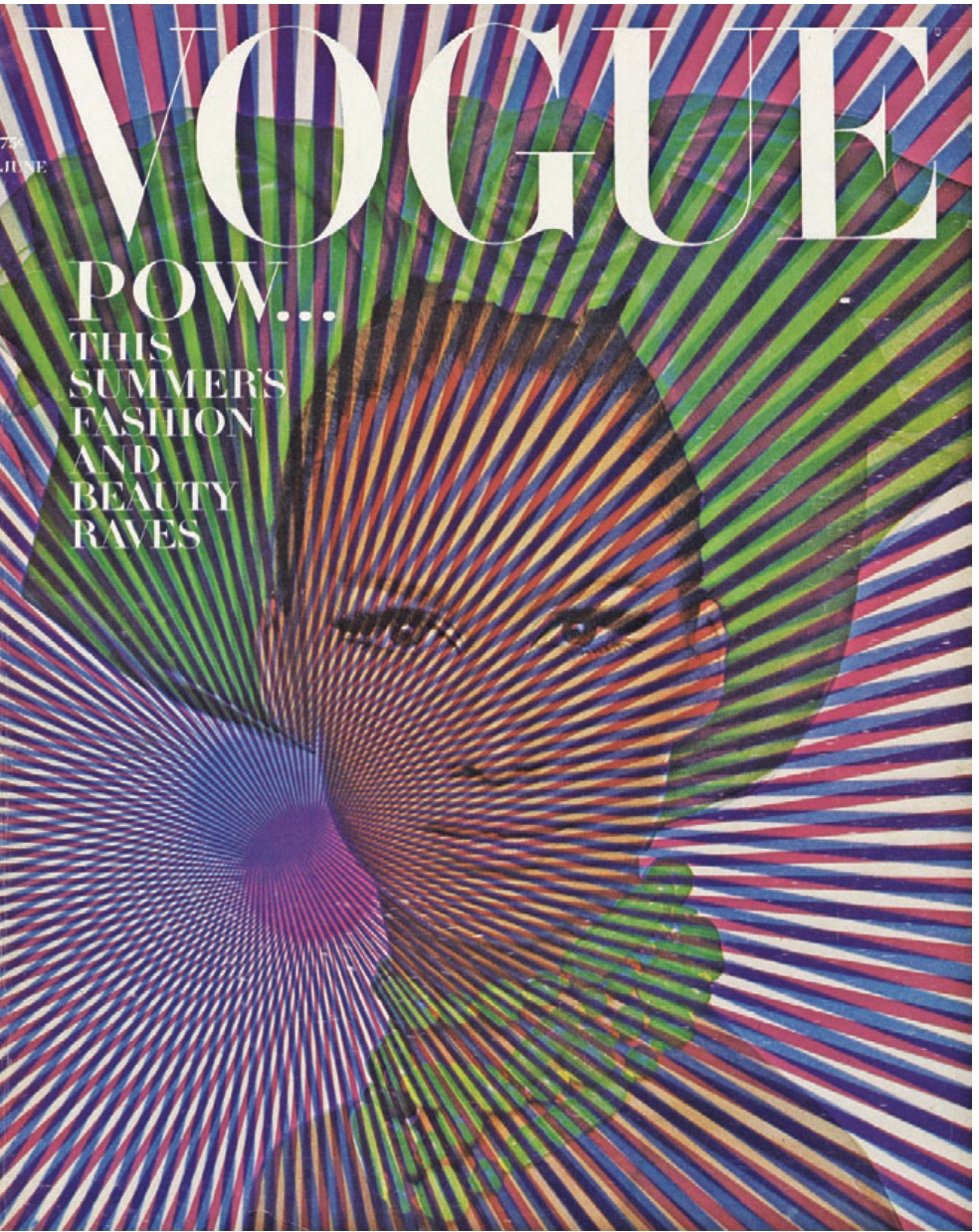

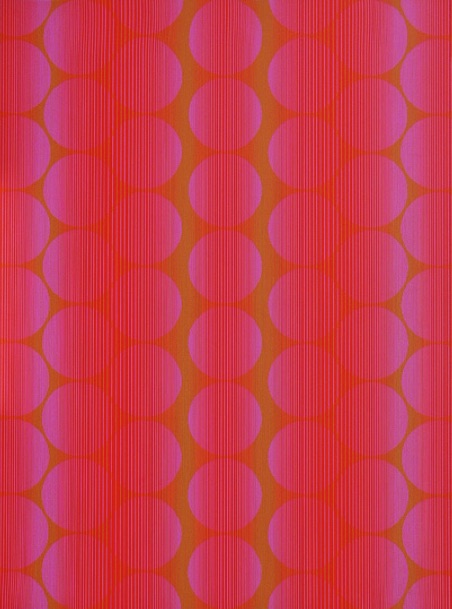

Current, the 1964 work by Bridget Riley, was featured on the cover of the exhibition catalog and it catapulted the artist to international art stardom. Just two months later, the cover of Vogue magazine was plastered with an Op-inspired swirling moiré pattern that seemed to retreat endlessly into the page, sparking the craze for psychedelic designs in Mod fashion.

The patterns generated by Riley and many other Op artists came to define this visual era, not least because Op artists’ concern with visual experience dovetailed neatly with a rising interest in the mind-bending properties of hallucinogenic drugs. All in all, the show was immensely popular and its hypnotic allure had a significant cultural impact in the arenas of fashion, design, and advertising.

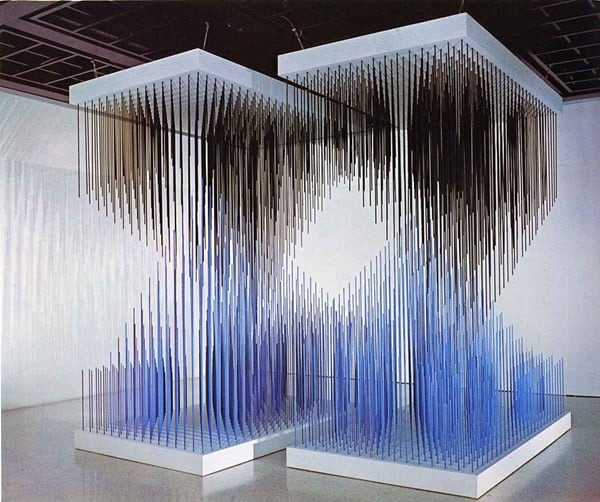

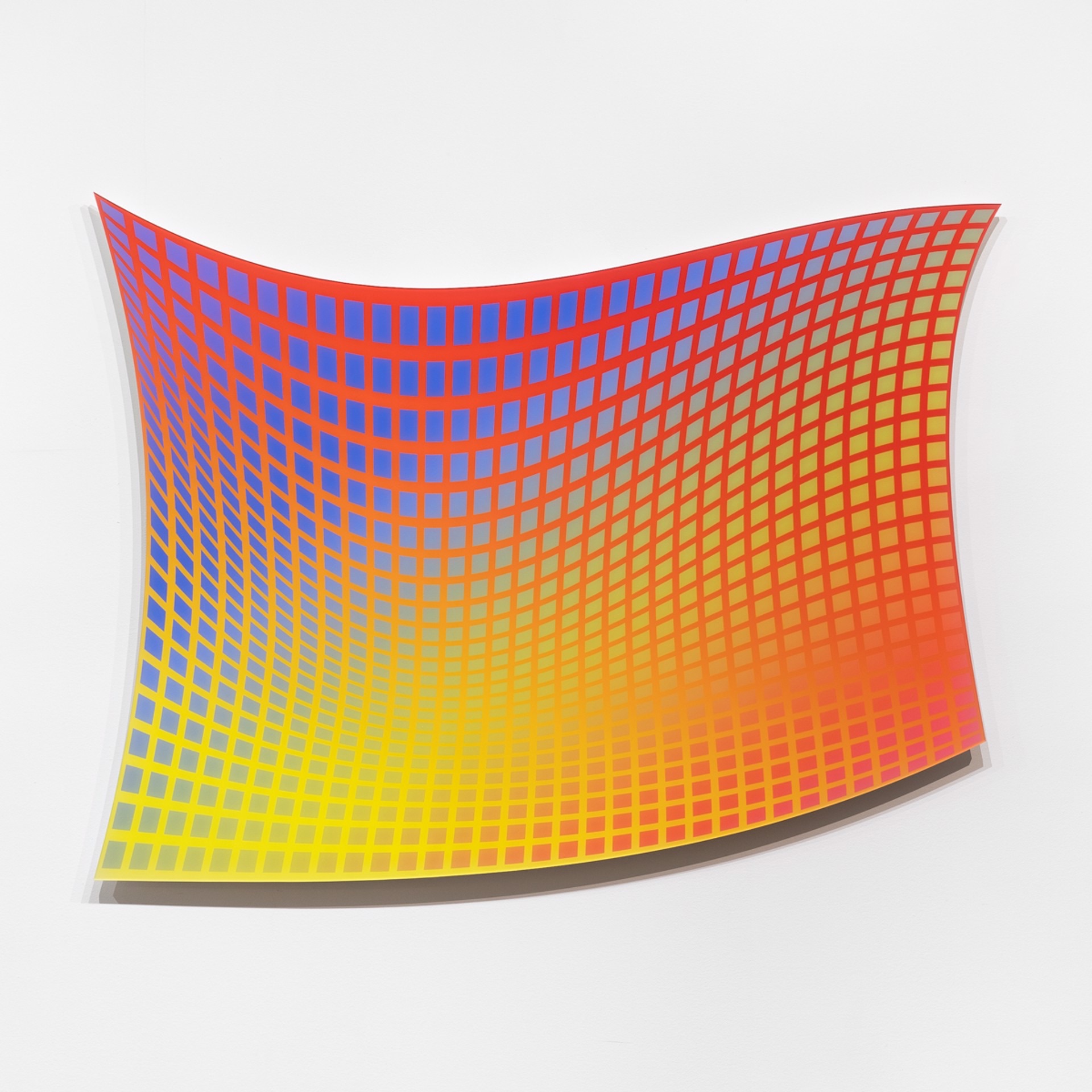

A Venezuelan contingent of Op artists, including Jesús Rafael Soto and Carlos Cruz-Diez, moved the early color experimentation of Albers and Vasarely into new mediums. Soto is known for using metal wires and rods to mimic the Moiré effect, while Cruz-Diez composes relief sculptures out of raised strips of aluminum that trap light to generate colors that aren’t actually present on the surface.

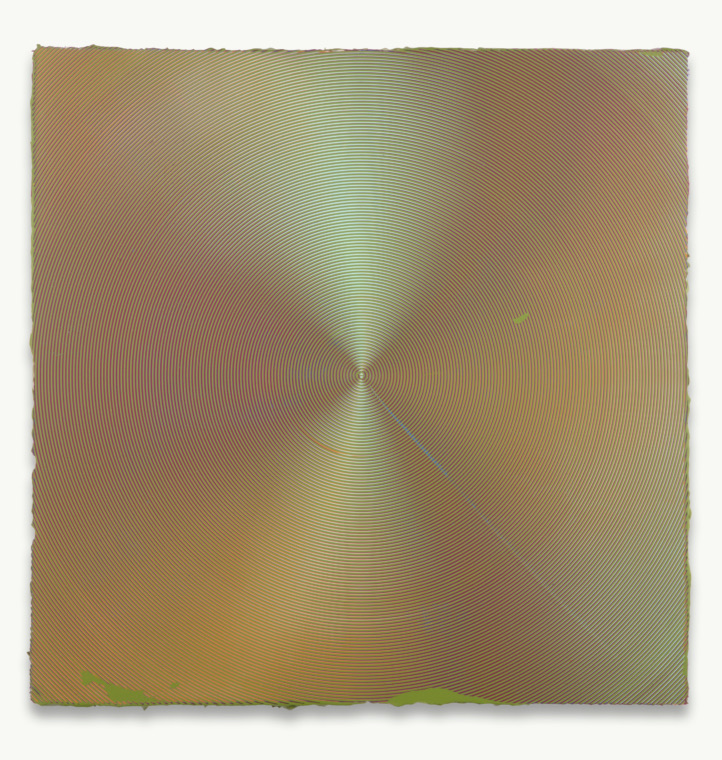

Despite its blurry boundaries, Op’s reach has been vast and the style is witnessing a distinct resurgence. Artist Peter Kogler has worked for the past twenty years toward expanding the work of the ‘60s into three-dimensional landscapes. Ultra-Contemporary artists like Julie Oppermann and Anoka Faruqee have honed in on the Moiré effect, inspired by qualities of digital images like modularity, optical flicker, and glitching.

If you’re interested in other works by these artists or want to hear more about how contemporary artists are using Op Art techniques, don’t hesitate to reach out!