How the Season Shapes the Way We See Art

As the calendar turns and winter’s hush settles across landscapes, there is a palpable shift – not just in light and temperature, but in the very way we perceive the world. Winter has long been a muse for artists, inviting reflection on stillness, contrast, endurance, and even joy. From the snowflake-dotted panels of the Northern Renaissance to the vibrant abstractions of modern painters, winter’s imprint on art is both profound and enduring.

One of the earliest Western depictions to secure winter’s place in art history is Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in the Snow (1565). Set against the chill of the Little Ice Age, Bruegel condenses the season’s stark beauty and daily toil – hunters crossing deep snow while villagers skate, chop wood and tend routines across a frozen valley – balancing severity with communal resilience. That sensibility is refracted centuries later in Claude Monet’s The Magpie (1868-1869), where subtle shifts of light across snow – blues and violets dancing with shadow – are rendered as a study in atmosphere and technique, signaling a decisive move toward modern perceptions of weather, colour and sensation.

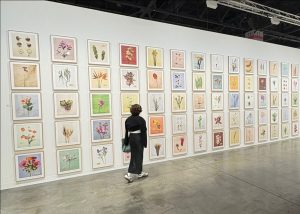

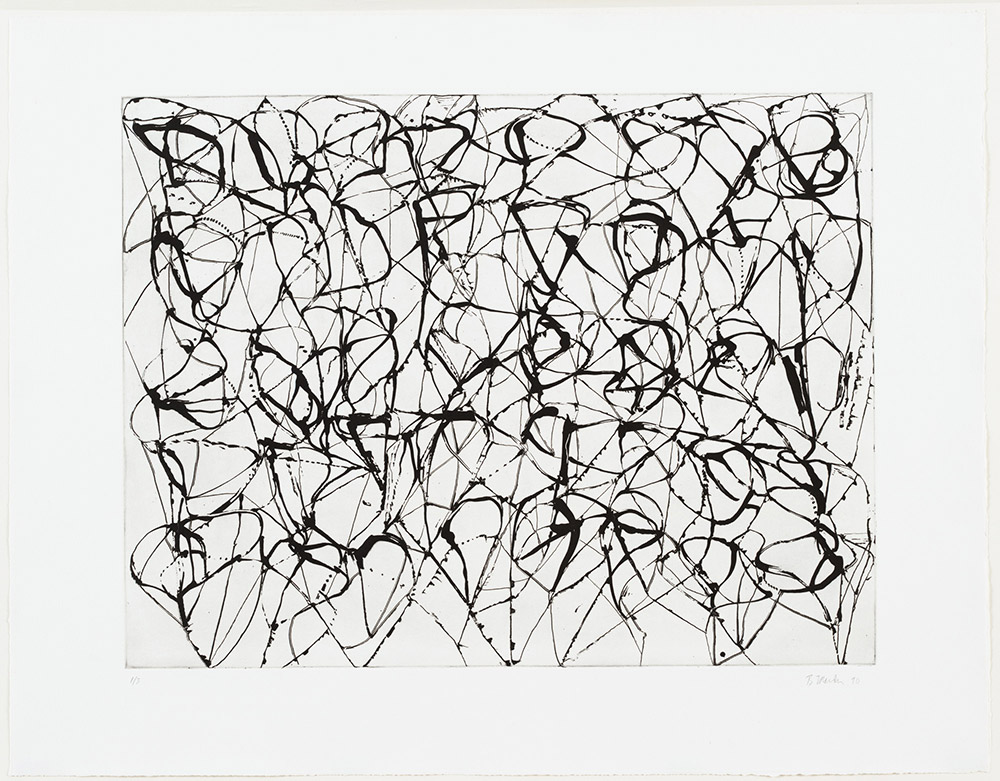

Winter’s emotional terrain continued to stir artists through the twentieth and into the twenty-first century, as winter’s imagery moved from representation toward abstraction and intimate, personal expression. Brice Marden’s Cold Mountain series, with its restrained palette and fluid, layered lines, evokes the quietude and subtle rhythms of winter, translating seasonal atmosphere into contemplative abstraction. Meanwhile, photographers such as Slim Aarons reframed winter as an arena of leisure and refinement – Winter Wear (1976) and Verbier Vacation (1964) celebrate the season’s sociable glamour rather than its severity. In contemporary practice, then, winter often functions less as a subject than as a metaphor: a season of transformation that reveals the quiet, underlying rhythms beneath a world temporarily hushed by cold.

Here in Canada, winter is an elemental force woven into cultural identity. The Winter Count: Embracing the Cold exhibition at the National Gallery of Canada, on view until 22 March 2026, brings together Indigenous, settler and European perspectives to show how deeply seasonal rhythms shape artistic expression. Works by Group of Seven figures such as Lawren Harris and A.Y. Jackson, who famously camped out and painted sketches on panels en plein air before reworking those impressions into larger studio canvases, sit alongside earlier chroniclers like Cornelius Krieghoff. Together, these artists form a distinctly Canadian vocabulary of winter.

What makes winter such a compelling artistic theme is not solely its whiteness or chill, but its ability to heighten contrast – light and shadow, solitude and community, endurance and celebration. Winter strips away leaves, colour and distraction, leaving the essence of form and feeling. In doing so, it challenges artists and viewers alike to see beneath surface appearances.

As we embrace this season once more, let us consider how winter changes what we see, not only in art but in life. The quiet of snow invites focus; the clarity of cold sharpens vision. In Montreal, the late John Little captured this heightened awareness through street scenes and skating rinks that have become enduring emblems of the city’s winter, preserving everyday rituals and architectural character with quiet luminosity. Whether you are an art connoisseur tracing the lineage of winter landscapes or a casual observer captivated by snowfall’s ephemeral beauty, winter remains an inexhaustible source of artistic inspiration, its stories as layered and luminous as fresh snow under the midday sun.

Here’s to a year where every season invites deeper seeing, starting with winter’s own extraordinary lens. If this moment of pause sparks a question, a curiosity, or the beginning of a collecting journey, we invite you to connect with us and continue the conversation.